Huawei, the crown jewel of China’s tech industry, is reeling from a financial one-two punch delivered by US chip sanctions and a campaign aimed at cutting international markets.

But with Huawei rapidly expanding into new markets and the Chinese government investing heavily to gain technological independence from the West, that leverage may not last for long.

The US government has targeted Huawei over alleged espionage and ties to the state, claiming that the company’s 5G wireless equipment poses a security risk. The rise of Chinese companies is viewed by many in the West as linked to the Chinese government’s power and its brand of techno-authoritarianism.

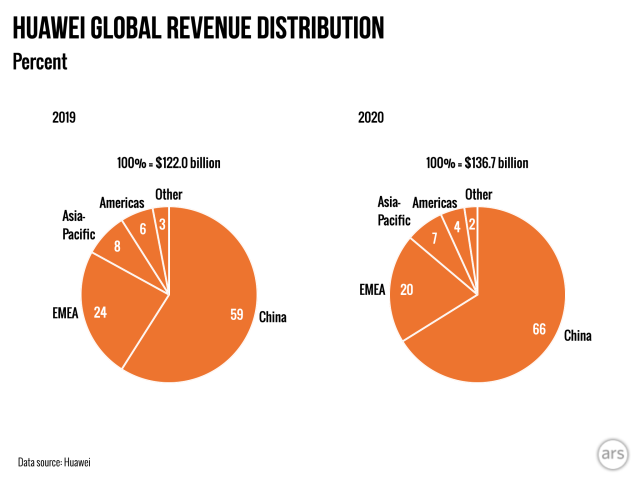

Huawei’s latest financial report, issued Wednesday, shows the financial cost of the US campaign. Revenue growth slowed to 3.8 percent last year, from 19 percent in 2019; international sales dropped sharply, especially in Europe.

The company’s smartphone sales have taken a big hit. Having ranked second in worldwide shipments behind Samsung in 2019, Huawei fell outside of the top five smartphone makers at the end of 2020, according to research firm Canalys.

“The US has been successful in checking the overall growth of Huawei, but it's doubtful it will crush it as a global technology power,” says Peter Cowhey, dean of the School of Global Policy & Strategy at UC San Diego and a former US government official.

The US has banned Huawei networking equipment from domestic 5G networks and persuaded other countries, including the UK, Canada, and Australia, to impose similar restrictions. Last year, the US also imposed export controls to cut off the supply of high-end chips to Huawei and advanced chipmaking equipment to China, effectively crippling Huawei’s ability to make high-end smartphones.

“The supply restrictions for our smartphone business has caused us a great impact, and we haven’t been able to see a clear picture in the supply for our smartphones,” Ken Hu, a Huawei deputy chairman, said at a press conference held at the company’s headquarters in Shenzhen on Wednesday. “We think this is a very unfair situation to Huawei, and it has caused a lot of damage to us.”

Microchips are China’s Achilles’ heel, because it doesn’t have domestic capability to make the nanoscale features found on the most advanced and most powerful of these components. Chinese chipmakers such as SMIC produce chips for lower-end products, including internet-of-things devices.

The only companies capable of manufacturing high-end chips today are located in Taiwan, South Korea, and the US. China has spent decades, and billions, trying to build up its chipmaking capabilities, but its most-advanced companies still lag several generations behind.

Now, China’s leaders are making a renewed push. Beijing’s Made in China 2025 plan, announced in 2014, calls for China to have a dominant position in chipmaking by 2049. The country’s latest five-year plan, announced in March, calls for increasing spending on research and development by 7 percent annually for the next five years, with a special focus on increasing technological independence in semiconductor manufacturing and other emerging technologies.

This week, the Chinese government also announced cuts to import taxes on raw materials for domestic companies producing high-end computer chips. This follows a wide range of tax breaks for semiconductor companies announced by the government in July 2020.

China has ample capital, raw materials, and engineering talent, and companies like Huawei, Alibaba, and Baidu are capable of designing cutting-edge chips. But China also lacks expertise specific to advanced chip manufacturing as well as the highly specialized equipment needed to make the latest chips.

A report issued in January by the Brookings Institution, a think tank, concludes that China’s increasingly vibrant domestic chip industry is likely to advance more rapidly due to sanctions and the increased decoupling of the US and China.

Another report, published in September 2020 by the Eurasia Group, a consultancy, suggests that the pressure China faces in chipmaking will encourage Chinese companies to explore new chip architectures.

Cowhey, who studies the intersection of telecommunications and governance, says Huawei’s size and breadth are helping it pivot into new areas.

“Network equipment [sales] have stalled substantially, and it’s true that its mobile phone division is in trouble,” he says. “But the growth of laptop computers, smartwatches, and other things really speak to its continued strength in the internet of things.”

A key question for policymakers in the US and other countries is how to most effectively counter the threat posed by Chinese technology and influence, and challenge the country on key issues such as human rights.

This story originally appeared on wired.com.

The Link LonkApril 03, 2021 at 06:15PM

https://ift.tt/3dtTLjH

US sanctions are squeezing Huawei, but for how long? - Ars Technica

https://ift.tt/3eIwkCL

Huawei

No comments:

Post a Comment